Blog

Sumbiography

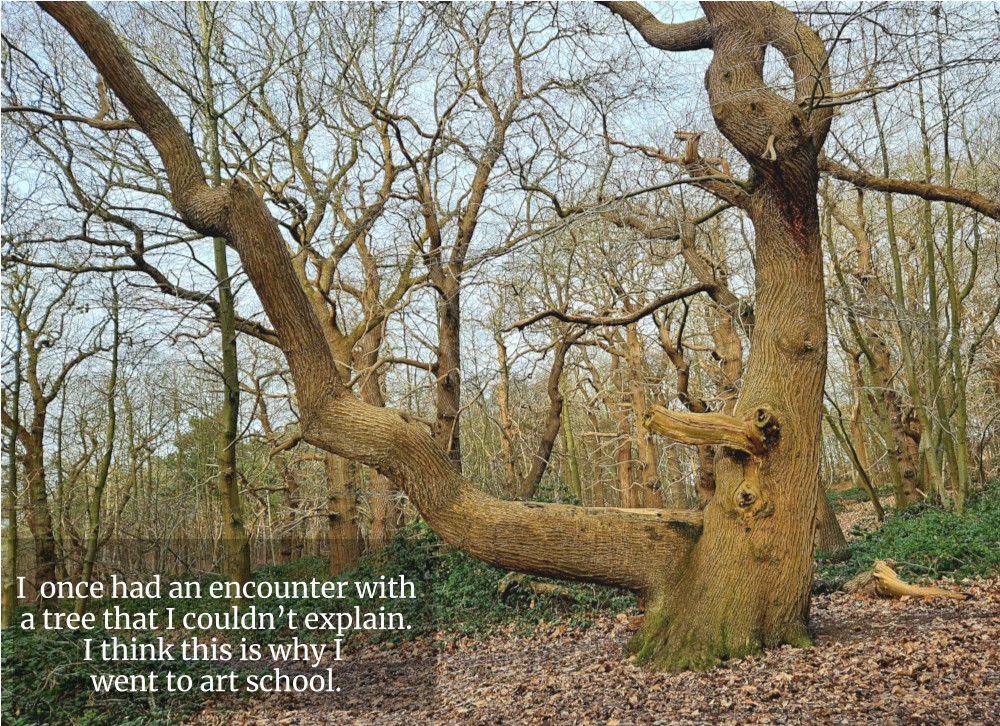

I once had an encounter with a tree that I couldn’t explain.

I think this is why I went to art school.

The term “sumbiography” was coined by Australian environmentalist Glenn Albrecht to refer to the collection of life experiences, from childhood to adulthood, that shape a person’s perspective on the relationship between humans, other living beings, and nature. [1] I was introduced to the term by Bridget McKenzie (of Climate Museum UK, and Culture Declares Emergency) as part of her excellent Earth Talk series. She suggested that as a brief introductory exercise, participants in the group—who have gathered to learn from her work about responding to Earth crisis—could reflect on what their own sumbiography would include.

As someone who always struggles to provide a sensible professional bio, Bridget’s prompt to write a sumbiography has been a very pleasurable exercise, reminding me of the seemingly miraculous encounters and lively connections that influence my outlook, and drive my work. Every evening for a week I retrieved and reflected on one experience from my childhood memory.

In doing so, I discovered that encounters with different life-forms and landscapes were deeply embedded in family life. Creatures played (or were made to play) many roles in my childhood—friends, enchanters, musicians, pets, tormentors, workers, family members, quarry, cultural trophies, muses, food sources, inspirations, and mysterious beings.

One (remembered) photo stands out: I am twelve years old, holding a snail on a leaf. I look happy, curious, proud, and also maybe a little shy—presenting it as if it were a fascinating new best friend.

The Catlows weren’t really pet people. Dad still pats the heads of dogs nervously with a stiff hand. My Great Aunt Jean found cats deeply unsettling, or in her words, “itchycoo”. She loathed them weaving and purring in a figure of eight around her ankles. Of course, cats adored her.

In Cumbria, where I spent weeks of the Summer at my Grandparents’ place with my brother – My uncle William had Springer Spaniels. They were not pets but working dogs, sent to fetch pheasants shot from the sky for sport. My grandmother Connie, would complain when they returned from a hunt and ran, all wet and floppy with mud, around the house. But she would still brew them a pot of tea and pour it, with a splash of milk, into their bowls, bestowing them the status of hardworking family members.

Aunt Lizzie loved birds, she had shelves full of books containing delicate and expressive drawings of them. Lizzie would complain bitterly about the pheasants hanging lifeless in the kitchen. Uncle William would meet her dismayed cries of disapproval — half objection, half horror — with disdainful sneers, casting them as sentimental, feeble, and irrelevant. In my memory, these repeated disagreements take place, out of time, against a background of curlews’ mournful calls curving upwards in low overlapping whistles through the drizzle in the mists across the sands at Grange.

Food was another arena where these tensions played out. Connie strongly disapproved of my vegetarianism. She had no hesitation in letting me know that she regarded it as a Southern affectation, and a perverse betrayal of my Catholicism and my God-given dominion, as a human, over all creatures of the Earth.

Only now, can I guess at Connie’s secret despair when I rejected meat over factory farming. What on earth would she feed me? After all, a meat dish with a good strong gravy, was her language of love: steak and kidney pie, Lancashire hot pot, shepherd’s pie, a roasted chicken, or joint of pork, or lamb. Then we could look forward to the cold cuts in the next day’s picnic featuring great chunks of meat in floury white baps, with slabs of butter, and mayonnaise, or mustard, or mint. On Carmell Fell, or out on one of the high mountains of the Lake District I would sit with Matt and my cousin Jane on some huge granite rock, munching happily.

Great Aunt Jean was a good person — steady, morally upright, a primary school head mistress devoted to the well-being of others. Her garden in Waddington, Lancashire, stretched long and narrow, with a winding path that led through an arch of pink climbing roses down to a tiny brook. The soft fluting calls of the wood pigeons filled the air, as if in a story. Even now, every wood pigeon song I hear evokes those remembered feelings of faith, grace, and safety that I felt in my Auntie Jean’s garden.

Amid these family dynamics I once had an encounter with a tree that I couldn’t explain. I would need to dedicate myself to exploring it further. I think this is why I became an artist.

On a visit to Porthleven as an art student, newly arrived in Cornwall from London, I watched the black crows hurling themselves into spiralling jets of wind at Loe Bar. The sea roared and pounded the steep pebble shore like a relentless and wild war drum. Beyond the Bar, the surface of the freshwater lagoon was a still black mirror. This scene still embodies for me life’s great mystery—the simultaneous existence, and contrast between worldly tumult and the infinite potential of inner stillness.

Since 2019, against the backdrop of mass species extinctions, we at Furtherfield have been working with creatures as mentors, using participatory role-play experiences to explore interspecies justice and governance. It’s serious play that sensitises me to the mysterious and inexplicable things that happen around us all the time.

Last year I went for a swim in my home town. Gorgeous hot day. Sparkling sea. Big swell. I found myself paying attention to the seagulls. Like you do in meditation – observing their movements, the way they fly together and across each other. Listening to their wheezy cries. Then one swooped down and dropped a £20 note on a wave right in front of me!

[1] Albrecht also coined the terms “sostalgia” for the emotional distress suffered as a result of negatively perceived environmental change, and “symbioscene” a proposed future era where humans live, emotionally, psychologically and technologically in harmony with the natural world.

Recent Comments